The communist era, generally viewed as a time of suffering and oppression, was a period of liberating exploration and unbelievable feats of bravery and persistence for one group: Poland’s mountain climbing community. Dramatically, many lost their lives in pursuit of glory. What was it that drove their extreme expeditions?

One of the stories from this article is also available in an audio format. Click the player below to listen to our podcast Stories From The Eastern West about how Wanda Rutkiewicz changed the world’s deadliest sport…

A daring generation

During the 1980s and 1990s, Polish mountain climbers flocked en masse to the Himalayan mountains in the hope of scaling some of the tallest and most difficult peaks in the world. Not only were they successful, but they also came to dominate the Himalayan climbing scene for the greater part of these two decades. Many of the finest mountain climbers in history emerged from this ambitious group of Poles: Andrzej Zawada, Jerzy Kukuczka, Krzysztof Wielecki, Wojciech Kurtyka, and Wanda Rutkiewicz.

For the majority of the population that would never dare attempt a feat as dangerous as mountain-climbing, it is hard to understand precisely what drove these people to the top of the world. Why would anyone with even a rudimentary understanding of statistics purposely tread the ever-so-thin line between life and death?

Was it the thrill of being at the cruising altitude of a commercial airline? Did climbing to dizzying heights and reaching the top of the world help to satisfy one’s ego? Was it a spiritual journey, akin to that of Jesus or Buddha? Was it merely the pursuit of the freedom many of these climbers had never experienced?

Or, to put it bluntly, is it just something that the faint of heart will never fully comprehend?

Using Bernadette McDonald’s remarkable book Freedom Climbers as a basis, we try to find out.

Made for climbing

Climbing worked like a drug on her. She never even gave it any consideration. It automatically entered her blood and was totally absorbed by it.

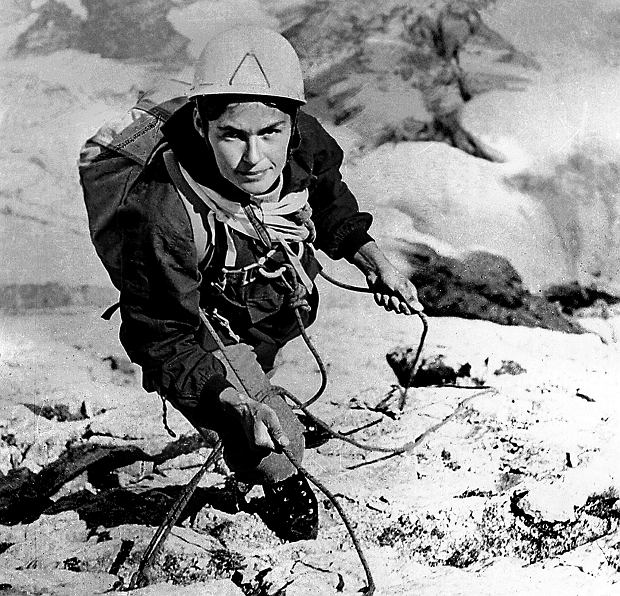

Climbing came naturally to Wanda Rutkiewicz. She was introduced to the sport by one of her school friends while she attended university in Wrocław and it was apparent from the first climb that she had a gift. She climbed efficiently and effortlessly. Her body was seemingly built for it. In her journal, she wrote:

I adored the physical movement, the fresh air, the camaraderie, and the excitement.

Yet, the small crags, trees, and chimneys she climbed in her university days could not in any way satisfy Wanda’s adventurous spirit. She had grown to love climbing, but as she became more experienced, her ambitions grew and as her ambitions grew, so did the obstacles she climbed. It was only natural that she would eventually be drawn to the mountains.

Soon after discovering her knack for mountain climbing, her career began to flourish. Before long, she became one of the most well-known and talented climbers in all of Poland. At one point she was even approached by the Polish secret service, who recognised her natural talent and believed she could be of great use to the communist state. However, her strong-willed personality and fiercely individualistic worldview meant that surrendering herself to the will of the regime was out of the question.

Following her swift rise to prominence, Wanda, in addition to attracting attention from Polish intelligence, began to impress many within the Polish mountain climbing community. Poland’s most skilled climbers immediately recognised her undeniable talent and potential. Andrzej Zawada, one of the leaders of this talented generation, decided to invite her on an expedition to the Soviet Pamirs, which would be her first major expedition.

The expedition was, however, an unpleasant experience for Wanda. She loathed the abasing treatment she received from male climbers and felt as though she wasn’t treated as an equal. Moreover, her confrontational personality and her inability to form and maintain relationships, problems that plagued her throughout her career, became apparent during this expedition.

After the Pamirs, she became convinced that her sponsors had essentially forced her to forfeit her independence. As had been shown by her encounter with the communist intelligence officials, such a forfeiture was anathema to her. She no longer wanted to participate in expeditions that caused her to lose her independence. She had to do things her way, even if that meant leading her own expeditions.

Climbing under communism

Most sporting competitions and competitive pursuits during the height of the Cold War became incredibly politicised. For Poland, mountain climbing was hardly an exception.

Mountain climbing had previously suffered due to acrimonious Russian-Polish relations, but the thaw in relations in the 1960s between the leaders Khruschev and Gomułka allowed for its resurgence. This thaw in relations made travelling far easier and allowed climbers access to peaks and ranges that were previously inaccessible.

The communist government recognised the potential of its mountain climbing community. It believed the success of its climbers could be exploited and used as a political tool that could help to legitimise and bolster support for the regime.

More importantly, the government believed that the success of their climbers would bring glory to Poland. For this reason, it was incredibly supportive of the climbers and their pursuits. Over time, as the mountain climbing community grew in size, a sizeable bureaucratic apparatus formed to subsidise their increasingly expensive expeditions.

At the same time, this fervent support for mountain-climbing does seem a bit ironic. It did bring Poland glory and put them on the world stage, that much is true, but mountain climbing itself is fundamentally un-communist.

In many cases, it was an individualistic pursuit, which clashed with the lofty communist notion of collectivism. Moreover, there was a truly liberating aspect to these expeditions. Once they entered the mountains, they were no longer under constant surveillance and subject to the authoritarian laws of their government. The mountains were, unbeknownst to the regime, a veritable oasis of freedom.

Communist officials, however, were not interested in analysing the deeper meaning of mountain climbing. All they cared about was that Poland was glorified on the international stage. And these climbers, whether intentional or not, undoubtedly succeeded in bringing glory to Poland.

Triumph

It is hard to say exactly what led to such a talented generation of Polish climbers. Some believed that the suffering Poland endured during the 20th century had created a resilient and driven group of people. Poles, however, believed that their success in the mountains came from a tradition of nobility and bravery that was inherent to their culture. Regardless of the source of their success, it was clear that these climbers were uniquely gifted.

During the 1980s and 1990s, Polish mountain climbers were among the most successful in the world. They managed to scale some of the world’s most difficult peaks, attempt increasingly dangerous routes, and challenge the limits of possibility.

It would be impossible to include all the accomplishments of Polish climbers during this period, but here is a list of some of their noteworthy achievements:

- In 1980, Andrzej Zawada led the first winter ascent of Mt. Everest.

- In 1985, Wojtek Kurtyka successfully climbed the ‘Shining Wall’ of the Gasherbrum IV peak in the Himalayas, a feat which some called one of the greatest achievements of mountaineering in the 20th century.

- In 1987, Jerzy Kukuczka became the second person to climb all fourteen ‘eight-thousanders’, the aptly-named peaks that tower over eight-thousand metres above sea-level.

- Kukuczka also created a new route on K2, dubbed the Polish Line, which no one has repeated.

- Krzysztof Wielecki became the fifth man to climb all fourteen eight-thousanders and the first person to climb Mt. Everest, Kangchenjunga, and Lhotse in the winter.

- Rutkiewicz became the first woman to summit K2 and the first Polish person, male or female, to climb Mt. Everest.

- Rutkiewicz also managed to climb eight of the fourteen eight-thousanders during her illustrious career.

It goes without saying that this was a particularly tenacious group of climbers. Not only did they scale some of the most daunting peaks in the world, they often did so in extremely difficult conditions. If a certain peak had already been summited numerous times, they looked for more challenging routes or scaled it in the dead of winter. In some cases, they even climbed alone or refused to use supplemental oxygen.

For these climbers, there would be always uncharted territory. There would always be a new record to break and a more challenging route to attempt. It was precisely this relentless determination and pioneering spirit that allowed them to be among the best in the world.

Wanda’s struggles

As Wanda became more popular and her achievements started to accumulate, she became increasingly isolated from the mountain climbing community. She had proved she was among the best in the world and her scaling of Mt. Everest became, arguably, her crowning achievement.

She also had led several all-female expeditions and became a trailblazer for women’s climbing throughout the world. She was one of, if not the most, recognisable mountain climbers in the world. As Rudolf Messner, arguably the greatest mountaineer in history, once said:

Wanda is the living proof that women can put up performances at high altitude that most men can only dream of.

Yet, this success does not tell the entire story. Many of these triumphs and achievements came at a significant cost to both her personal life and her relationships with other climbers.

For one, the schedule of a mountain climber can be rather erratic. Wanda’s obsession with the pursuit only managed to exacerbate this. Since she was away from home for so long her marriages suffered, her finances were in shambles, and her nomadic lifestyle was unmanageable.

The difficulties in her personal life coupled with the death of her father also made her distrustful by nature. As a result, she was wary of commitment and often pushed away those who wanted to help her. As one climber put it:

Difficult. Competing. We loved her but she didn’t seem to know that. She thought she was alone. She pushed us away. But we loved Wanda.

Unfortunately, many of these personal struggles followed her on expeditions and often manifested themselves in other difficulties. In some instances, her strong will demonstrated that she was as capable as any male climber, regardless of what they thought of her. As Krzysztof Wielecki, one of Poland’s most decorated climbers, said:

She was very calculating, tough like a bull.

Or on another occasion:

A difficult woman, an extraordinary woman.

In other instances, she became dictatorial in her leadership style, alienating many of her peers. Her determination instilled confidence in other climbers, but her leadership style, once again, hurt the relationships she frequently struggled to maintain.

It is important to add, however, that these personal struggles do not in any way diminish the significance of her accomplishments. On the contrary – when her personal struggles are taken into consideration, her accomplishments become even more admirable. They manage to demonstrate how resilient she truly was.

And despite the obstacles she faced, both in the mountains and back home, she nonetheless remained one of the most talented climbers of her generation and in the history of women’s climbing.

Filed under: Adventure Travel, Andrzej Bargiel, Andrzej Czok, Anna Czerwinska, Climbers, Everest, Expedition, Historically exp-tions, Jerzy Kukuczka, Karakoram, Kinga Baranowska, Krzysztof Wielicki, Leszek Cichy, Nepal, Pakistan, Piotr Morawski, Piotr Pustelnik, Polish Himalayas, Ryszard Pawłowski | Tagged: Anna Czerwinska, Climbers, Everest, Expedition, first winter ascent, golden decade, Himalaya, Ice Warriors, Jurek Kukuczka, Kinga Baranowska, Krzysztof Wielicki, Leszek Cichy, Maciej Berbeka, MARCIN MIOTK, Piotr Morawski, Piotr Pustelnik, Polish famous climbers, Ryszard Pawłowski, Wanda Rutkiewicz, winter expedition | Leave a comment »

K2 Photo: M. Chmielarski

K2 Photo: M. Chmielarski

Leave a Reply